SAFETY IN SPORT, THE HARD YARDS WAY - PART 2

I wrote an article back in October last year outlining our methodology for developing and testing our protective sportswear, you can find that here. I spoke about the issues with standardised impact testing, what our approach to this is, when it can be useful and when it is not, and even hinted at our partnership with the Innovation Department at Newcastle University and that we were working closely with them to test our guards to research standards. I’m really pleased to be able to tell you a little more about this project, a Part 2 of 3, and provide an update of where we are at.

Aims

Over the past 6 months, we finally managed to get back into the labs to test our guards and answer 4 key questions.

Do our current guards in stock still hit the mark in terms of protection? An internal quality control check.

To what extent does guard thickness and density influence protective capacity, without sacrificing comfort? Should we consider adjusting these parameters for our next batch?

Does a polycarbonate shell make a difference to impact absorption?

How do Hard Yards guards compare to our competitor’s?

Methods

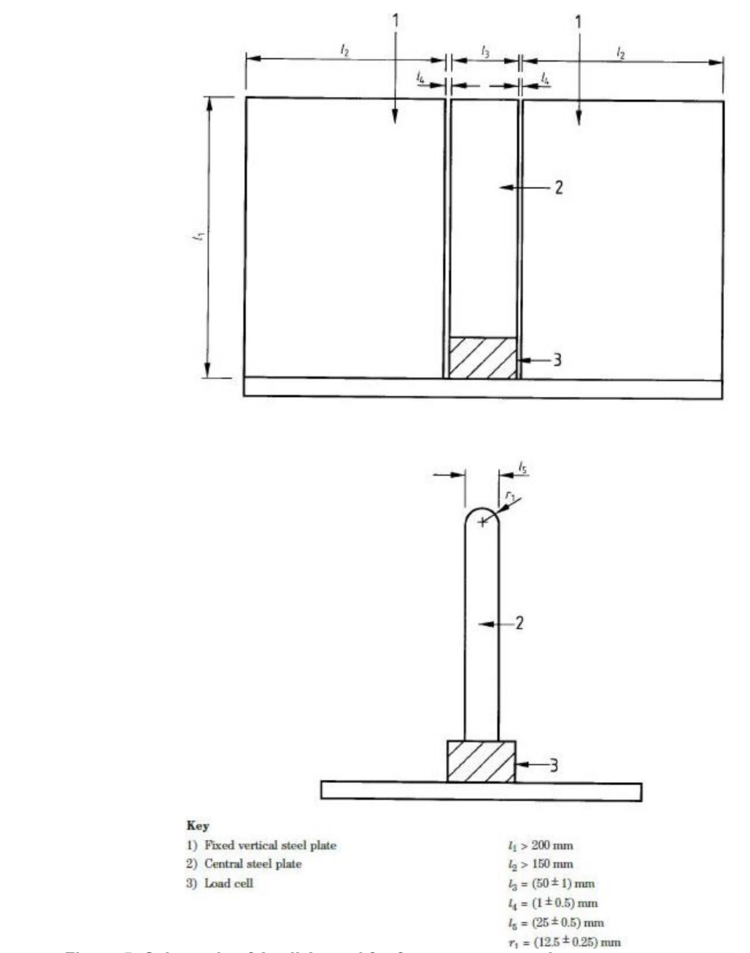

For this testing round (despite my issues with it in Part 1!) it was necessary to control as much about the testing environment and apparatus as possible, and so we chose to replicate the British Standard format. We set up the rig you can see in the right-top image, essentially replicating the British Standard set-up (right-bottom). This ensured that each test would be the same, repeatable and gave a fair representation of what is actually happening in the guards, this optimising our results for both accuracy and precision. The only variable therefore was the guard itself.

Results

So, what about the results, as I know that’s why you are here! I have kept the numbering for our results and discussion sections consistent with each question above →

Our current guards held up as expected to the Level 3 British Standard, this is the highest level for arm guards.

We tested a range of thicknesses from 3mm to 10mm and densities of 20% to 40%. Anything outside of these ranges was either impractically cumbersome, too stiff to conform to the arm, or simply not fit for protective purposes.

There was a definite correlation between guard thickness and protective capacity. It was a repeatable difference of ~500-1000 Newtons of force between the thinnest and thickest guards.

Density however, surprisingly had minimal effect.

Applying a polycarbonate (or similar thermoplastic polymer) shell to the outside of the flexible foam guard does not improve impact protection, and in some tests actually made it less good at absorbing impact force.

Under these testing conditions, there was no statistically significant difference between the Hard Yards guard material and our direct competitors in terms of impact protection for the same thickness of guard. Here is an extract from our testing data.

Discussion

Quality Control

We were really pleased to see that our guards are still meeting the highest testing spec. Clearly, consistency between guards is good, thumbs up to the manufacturers!

Guard thickness

It wasn’t too surprising to see that the thickness of our guards directly correlates with impact protection. Subjectively we felt that this would be the case, but it was still important to bare this out in the data. While this data-set is definitely encouraging, you (and we) should not take this as gospel and that it tells us to how your arm will feel when being hit by a cricket, hockey or lacrosse ball, and you shouldn’t be convinced by anyone who shows you a graph like this and tells you as such. All it shows is that it meets the British Standard and it’s not possible to reasonably extrapolate this data out to real-world sporting conditions or make marketing claims around it. The British Standard does however give us confidence that it reduces impact in a meaningful way and that it does so in a consistent manner without degradation over repeated impacts, but you can’t say what speed of ball it will protect you from or how it will feel, for example. Cricket, hockey and lacrosse balls are all smaller, lighter, and move much faster. Your forearms generally have a more broad impact zone with additional ‘built-in’ cushioning in the form of fat and muscle, and indeed, arms are not fixed objects. All these variables change from person to person, ball to ball and so anyone who tells you that their guard is the best at protecting you from ball-related sporting injuries using this type of data is simply sticking their thumb in the air and hoping you’ll accept the nice graphs as definitive proof that they meet your specific sporting needs. That being said it does provide a degree of scientific confidence and, backed up by anecdotal performance from professional players, we feel confident they do the job, but we’d like to go further.

Guard Density

What did surprise us however is that density did not have much of an effect on impact. Our current guards sit at 43% density and we chose this as it sits right at the higher end without compromising on flexibility and comfort; our hypothesised sweet-spot. While testing densities between 20%-40% showed an observable correlation with impact protection from a raw data perspective, this was statistically non-significant under these testing conditions. In our minds, it would make sense to use the lowest density we can to achieve the necessary impact protection. This prevents material wastage and there is a subjectively noticeable difference to the weight and flexibility of the guard, all good things. In this case, it might be that under these standardised testing conditions, the true difference between 20% and 40% density was not observed, but under more realistic conditions, ie, high-speed impact with a cricket ball this difference might be seen more clearly. At this stage, we’ll continue to use the higher densities until further experimental testing is done.

Polycarbonate - the elephant in the room.

We noticed a while ago some arm guard manufacturers have opted to glue an additional thin polycarbonate (or other thermoplastic polymer) plate to the outside of their guard, aiming to improve protection beyond the standard guard. This is sometimes marketed as a ‘Pro’ version that will do a better job of protecting your arms from impact, targeting pro-game speeds.

Our testing showed with convincing repeatability that adding a polycarbonate plate does not improve the protective capabilities of any of the guards we tested. Some of the tests even showed a reduction in impact absorption.

This was a result we did not expect. I can honestly say that we really did not know if it would actually make a difference or not; our intuition said that a solid piece of polycarbonate should do something positive, but we don’t rely on intuition alone, and that’s precisely why we ran the tests. In some ways, we were quite disappointed as we were keen to potentially implement this into our own line-up of guards however following this testing, clearly this would be futile and without benefit to our athletes.

It’s not entirely clear why this might be happening. With non-Newtonian protective materials, impact force is reduced both by the molecular bonds dynamically strengthening in response to the impact, but also by decelerating the object through compression the material itself. When discussing with Dr Oila at Newcastle University (project supervisor) we felt that the most likely explanation at play is that the polycarbonate does not allow the non-Newtonian material underneath to compress, an action that is required for the guard to effectively dissipate the impact force over its full area.

Regardless of the explanation for why this may be occurring at the material science level, we can be confident that a polycarbonate shell is not beneficial and it is most likely only providing a placebo effect ie, it subjectively feels more solid and people may therefore feel it will provide better protection, even if this is not true in reality.

Hard Yards vs The World!

Last but not least, we were both pleased and (ever so slightly!) disappointed to see that of all arm guard brands tested that use a non-Newtonian material, protective capacity was largely the same when we controlled for guard thickness. The traditional guards (those using a HDPE or very thick spongy foam) did not fair well enough to include in the charts above.

Clearly, we’d love to tell you our guard material is the best in the market, but between the 2 guards that use a non-Newtonian material, they both protect to a very similar degree, likely imperceptible and probably not significantly different from a clinical perspective. While this is interesting in itself, it informs a lot more about how you should choose which brand to go with when purchasing a new arm guard, ie, don’t worry about the guard itself!

If optimised protection, flexibility and comfort is key, and you also want the option to change the level of protection, or to change the sweatband colour to suit your needs at the crease then we would recommend our patented High Impact Protective Guard as the best overall guard on the market at present!

However, if you absolutely need to have that subjective ‘feeling’ of a solid guard, we’d first urge you to give our guard a try, but there are some solid guards out there that do a comparable job at protecting your arm. Bear in mind however that it is just a feeling and carries no additional impact protection over their soft shell version, you are simply paying extra for the feeling and the overall comfort/breathability will be less good! In addition, other arm guards seal their guards into the sweatbands, so you won’t be able to adjust the protection level or change the colour so it will cost you far more in the long run.

Recommendations & Future work

Don’ buy into the marketing around ‘Pro’ versions with an added solid polycarbonate polycarbonate plate, unless you simply prefer the subjective feeling of a solid guard.

Overall, the Hard Yards High Impact Protective Guard offers the greatest overall benefit to our athletes’ performance in terms of flexibility, comfort and the ability to swap to different guard thicknesses or sweatband colours easily. Our patented design also means that if you want to upgrade, or replace a worn out component, you don’t need to buy a whole new set, you can simply buy an individual piece!

Moving forwards, we’ll be testing our guards further under more realistic match-play conditions using a custom rig and bowling machine. This will be to understand how the various differences in the data play at higher, more realistic speeds. Standby for Part 3!

Until next time!